Göbekli Tepe

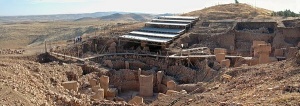

Göbekli Tepe (Turkish: [ɡøbe̞kli te̞pɛ], "Potbelly Hill"]) is an archaeological site at the top of a mountain ridge in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, approximately 12 km (7 mi) northeast of the city of Şanlıurfa. The tell has a height of 15 m (49 ft) and is about 300 m (984 ft) in diameter. It is approximately 760 m (2,493 ft) above sea level. It has been excavated by a German archaeological team that was under the direction of Klaus Schmidt from 1996 until his death in 2014.[1]

The tell includes two phases of ritual use dating back to the 10th-8th millennium BCE. During the first phase (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)), circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars were erected. More than 200 pillars in about 20 circles are currently known through geophysical surveys. Each pillar has a height of up to 6 m (20 ft) and a weight of up to 20 tons. They are fitted into sockets that were hewn out of the bedrock. In the second phase (Pre-pottery Neolithic B (PPNB)), the erected pillars are smaller and stood in rectangular rooms with floors of polished lime. Topographic scans have revealed that other structures next to the hill, awaiting excavation, probably date to 14-15 thousand years ago, the dates of which potentially extend backwards in time to the concluding millennia of the Pleistocene.The site was abandoned after the PPNB-period. Younger structures date to classical times.

The function of the structures is not yet clear. Excavator Klaus Schmidt believed that they are early neolithic sanctuaries.

Discovery

The site was first noted in a survey conducted by Istanbul University and the University of Chicago in 1963. American archaeologist Peter Benedict identified it as being possibly neolithic and postulated that the Neolithic layers were topped by Byzantine and Islamic cemeteries. The survey noted numerous flints. Huge limestone slabs, upper parts of the T-shaped pillars, were thought[by whom?] to be grave markers. The hill had long been under agricultural cultivation, and generations of local inhabitants had frequently moved rocks and placed them in clearance piles, possibly destroying archaeological evidence in the process.

In 1994, Klaus Schmidt, of the German Archaeological Institute, who had previously been working at Nevalı Çori, was looking for another site to lead a dig. He reviewed the archaeological literature on the surrounding area, found the Chicago researchers’ brief description of Göbekli Tepe, and decided to give it another look. With his knowledge of comparable objects at Nevalı Çori, he recognized the possibility that the rocks and slabs were parts of T-shaped pillars.

The following year, he began excavating there in collaboration with the Şanlıurfa Museum. Huge T-shaped pillars were soon discovered. Some had apparently been subjected to attempts at smashing, probably by farmers who mistook them for ordinary large rocks. The nearby Gürcütepe site - also Neolithic - was not excavated until 2000.[2]

The Complex

Göbekli Tepe is situated on a flat and barren plateau, with buildings fanning in all directions. In the north, the plateau is connected to a neighbouring mountain range by a narrow promontory. In all other directions, the ridge descends steeply into slopes and steep cliffs. On top of the ridge, there is considerable evidence of human impact in addition to the actual tell. Excavations have taken place at the southern slope of the tell, south and west of a mulberry that marks an Islamic pilgrimage, but archaeological finds come from the entire plateau. The team has also found many remains of tools.

Plateau

The plateau has been transformed by erosion and by quarrying, which took place not only in the Neolithic, but also in classical times. There are four 10 m (33 ft) long and 20 cm (8 in) wide channels on the southern part of the plateau, interpreted as the remains of an ancient quarry from which rectangular blocks were taken. These are possibly related to a square building in the neighbourhood, of which only the foundation is preserved. Presumably, this is the remains of a Roman watchtower which belonged to the Limes Arabicus. However, this is not known with certainty.

Most structures on the plateau seem to be the result of Neolithic quarrying, with the quarries being used as sources for the huge, monolithic architectural elements. Their profiles were pecked into the rock, with the detached blocks then levered out of the rock bank.[13] Several quarries where round workpieces had been produced were identified. Their status as quarries was confirmed by the find of a 3-by-3-metre piece at the southeastern slope of the plateau. Unequivocally Neolithic are three T-shaped pillars that have not been levered out of the bedrock. The biggest of them lies on the northern plateau. It has a length of 7 m (23 ft) and its head has a width of 3 m (10 ft). Its weight may be around 50 tons. The two other unfinished pillars lie on the southern Plateau.At the western edge of the hill, a lion-like figure was found. In this area, flint and limestone fragments occur more frequently. It was therefore suggested that this could have been some kind of sculpture workshop. It is unclear, on the other hand, how to classify three phallic depictions from the surface of the southern plateau. They are near the quarries from classical times, making their dating difficult.

Apart from the tell, there is an incised platform with two sockets that could have held pillars, and a surrounding flat bench. This platform corresponds to the complexes from Layer III at the actual tell. Continuing the naming pattern, it is called "complex E." Owing to its similarity to the cult-buildings at Nevalı Çori it has also been called "Temple of the Rock." Its floor has been carefully hewn out of the bedrock and smoothed, reminiscent of the terrazzo floors of the younger complexes at Göbekli Tepe. Immediately northwest of this area are two cistern-like pits, believed to be part of complex E. One of these pits has a table-high pin as well as a staircase with five steps.

At the western escarpment, a small cave has been discovered in which a small relief depicting a bovine was found. It is the only relief found in this cave.[3]

Chronological context

All statements about the site must be considered preliminary, as less than 5% of the site has been excavated, and Schmidt planned to leave much of it untouched to be explored by future generations (when archaeological techniques will presumably have improved). While the site formally belongs to the earliest Neolithic (PPNA), up to now no traces of domesticated plants or animals have been found. The inhabitants are assumed to have been hunters and gatherers who nevertheless lived in villages for at least part of the year. So far, very little evidence for residential use has been found. Through the radiocarbon method, the end of Layer III can be fixed at about 9000 BCE (see above) but it is believed that the elevated location may have functioned as a spiritual center by 11,000 BCE or even earlier.The surviving structures, then, not only predate pottery, metallurgy, and the invention of writing or the wheel, they were built before the so-called Neolithic Revolution, i.e., the beginning of agriculture and animal husbandry around 9000 BCE. But the construction of Göbekli Tepe implies organization of an advanced order not hitherto associated with Paleolithic, PPNA, or PPNB societies.

Archaeologists estimate that up to 500 persons were required to extract the heavy pillars from local quarries and move them 100–500 meters (330–1,640 ft) to the site. The pillars weigh 10–20 metric tons (10–20 long tons; 11–22 short tons), with one still in the quarry weighing 50 tons. It has been suggested that an elite class of religious leaders supervised the work and later controlled whatever ceremonies took place. If so, this would be the oldest known evidence for a priestly caste—much earlier than such social distinctions developed elsewhere in the Near East.

Around the beginning of the 8th millennium BCE Göbekli Tepe ("Potbelly Hill") lost its importance. The advent of agriculture and animal husbandry brought new realities to human life in the area, and the "Stone-age zoo" (Schmidt's phrase applied particularly to Layer III, Enclosure D) apparently lost whatever significance it had had for the region's older, foraging communities. But the complex was not simply abandoned and forgotten to be gradually destroyed by the elements. Instead, each enclosure was deliberately buried under as much as 300 to 500 cubic meters (390 to 650 cu yd) of refuse consisting mainly of small limestone fragments, stone vessels, and stone tools. Many animal, even human, bones have also been identified in the fill. Why the enclosures were buried is unknown, but it preserved them for posterity.

Schmidt's view, shared by most experts, was that Göbekli Tepe is a stone-age mountain sanctuary. Radiocarbon dating as well as comparative, stylistic analysis indicate that it is the oldest religious site yet discovered anywhere. Schmidt believed that what he called this "cathedral on a hill" was a pilgrimage destination attracting worshippers up to 100 miles (160 km) distant. Butchered bones found in large numbers from local game such as deer, gazelle, pigs, and geese have been identified as refuse from food hunted and cooked or otherwise prepared for the congregants.Schmidt considered Göbekli Tepe a central location for a cult of the dead and that the carved animals are there to protect the dead. Though no tombs or graves have been found so far, Schmidt believed that they remain to be discovered in niches located behind the sacred circles' walls. Schmidt also interpreted it in connection with the initial stages of the Neolithic. It is one of several sites in the vicinity of Karaca Dağ, an area which geneticists suspect may have been the original source of at least some of our cultivated grains (see Einkorn). Recent DNA analysis of modern domesticated wheat compared with wild wheat has shown that its DNA is closest in sequence to wild wheat found on Mount Karaca Dağ 20 miles (32 km) away from the site, suggesting that this is where modern wheat was first domesticated. Such scholars suggest that the Neolithic revolution, i.e., the beginnings of grain cultivation, took place here. Schmidt believed, as others do, that mobile groups in the area were compelled to cooperate with each other to protect early concentrations of wild cereals from wild animals (herds of gazelles and wild donkeys). Wild cereals may have been used for sustenance more intensively than before and were perhaps deliberately cultivated. This would have led to early social organization of various groups in the area of Göbekli Tepe.

Thus, according to Schmidt, the Neolithic did not begin on a small scale in the form of individual instances of garden cultivation, but developed rapidly in the form of "a large-scale social organization". Schmidt engaged in some speculation regarding the belief systems of the groups that created Göbekli Tepe, based on comparisons with other shrines and settlements. He assumed shamanic practices and suggested that the T-shaped pillars represent human forms, perhaps ancestors, whereas he saw a fully articulated belief in gods only developing later in Mesopotamia, associated with extensive temples and palaces. This corresponds well with an ancient Sumerian belief that agriculture, animal husbandry, and weaving were brought to mankind from the sacred mountain Ekur, which was inhabited by Annuna deities, very ancient gods without individual names. Schmidt identified this story as a primeval oriental myth that preserves a partial memory of the emerging Neolithic. It is also apparent that the animal and other images give no indication of organized violence, i.e. there are no depictions of hunting raids or wounded animals, and the pillar carvings ignore game on which the society mainly subsisted, like deer, mainly in favor of formidable creatures like lions, snakes, spiders, and scorpions.

Importance

Göbekli Tepe is regarded as an archaeological discovery of the greatest importance since it could profoundly change the understanding of a crucial stage in the development of human society. Ian Hodder of Stanford University said, "Göbekli Tepe changes everything".It shows that the erection of monumental complexes was within the capacities of hunter-gatherers and not only of sedentary farming communities as had been previously assumed. As excavator Klaus Schmidt put it, "First came the temple, then the city."

Not only its large dimensions, but the side-by-side existence of multiple pillar shrines makes the location unique. There are no comparable monumental complexes from its time. Nevalı Çori, a Neolithic settlement also excavated by the German Archaeological Institute and submerged by the Atatürk Dam since 1992, is 500 years later. Its T-shaped pillars are considerably smaller, and its shrine was located inside a village. The roughly contemporary architecture at Jericho is devoid of artistic merit or large-scale sculpture, and Çatalhöyük, perhaps the most famous Anatolian Neolithic village, is 2,000 years later.At present Göbekli Tepe raises more questions for archaeology and prehistory than it answers. It remains unknown how a force large enough to construct, augment, and maintain such a substantial complex was mobilized and compensated or fed in the conditions of pre-sedentary society. Scholars cannot interpret the pictograms, and do not know for certain what meaning the animal reliefs had for visitors to the site; the variety of fauna depicted, from lions and boars to birds and insects, makes any single explanation problematic. As there is little or no evidence of habitation, and the animals pictured are mainly predators, the stones may have been intended to stave off evils through some form of magic representation. Alternatively, they could have served as totems.

The assumption that the site was strictly cultic in purpose and not inhabited has also been challenged by the suggestion that the structures served as large communal houses, "similar in some ways to the large plank houses of the Northwest Coast of North America with their impressive house posts and totem poles." It is not known why every few decades the existing pillars were buried to be replaced by new stones as part of a smaller, concentric ring inside the older one. Human burial may or may not have occurred at the site. The reason the complex was carefully backfilled remains unexplained. Until more evidence is gathered, it is difficult to deduce anything certain about the originating culture or the site's significance.