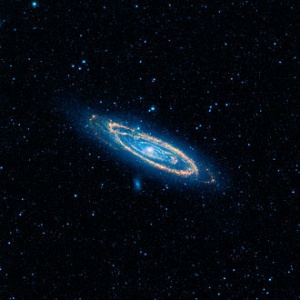

Messier 31

Andromeda Galaxy is a spiral galaxy approximately 780 kiloparsecs (2.5 million light-years; 2.4×1019 km) from Earth.Also known as Messier 31, M31, or NGC 224, it is often referred to as the Great Andromeda Nebula in older texts. The Andromeda Galaxy is the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way, but not the nearest galaxy overall. It gets its name from the area of the sky in which it appears, the constellation of Andromeda, which was named after the mythological princess Andromeda. The Andromeda Galaxy is the largest galaxy of theLocal Group, which also contains the Milky Way, the Triangulum Galaxy, and about 44 other smaller galaxies.

The Andromeda Galaxy is the most massive galaxy in the Local Group as well. Despite earlier findings that suggested that the Milky Way contains more dark matter and could be the most massive in the grouping, the 2006 observations by the Spitzer Space Telescope revealed that M31 contains one trillion (1012) stars:[9] at least twice the number of stars in the Milky Way, which is estimated to be 200–400 billion.[13] The Andromeda Galaxy is estimated to be 1.5×1012 solar masses, while the mass of the Milky Way is estimated to be 8.5×1011 solar masses. In comparison a 2009 study estimated that the Milky Way and M31 are about equal in mass, while a 2006 study put the mass of the Milky Way at ~80% of the mass of the Andromeda Galaxy. The two galaxies are expected to collide in 3.75 billion years, eventually merging to form a giant elliptical galaxy [15] or perhaps a large disk galaxy.

At 3.4, the apparent magnitude of the Andromeda Galaxy is one of the brightest of any Messier objects,[17] making it visible to the naked eye on moonless nights even when viewed from areas with moderate light pollution. Although it appears more than six times as wide as the full Moon when photographed through a larger telescope, only the brighter central region is visible to the naked eye or when viewed using binoculars or a small telescope. Charles Messier catalogued Andromeda as object M31 in 1764 and incorrectly credited Marius as the discoverer, unaware of Al Sufi's earlier work. In 1785, the astronomer William Herschel noted a faint reddish hue in the core region of M31. He believed M31 to be the nearest of all the "great nebulae" and based on the color and magnitude of the nebula, he incorrectly guessed that it was no more than 2,000 times the distance of Sirius. M31 plays an important role in galactic studies, since it is the nearest spiral galaxy (although not the nearest galaxy). In 1943 Walter Baade was the first person to resolve stars in the central region of the Andromeda Galaxy. Based on his observations of this galaxy, he was able to discern two distinct populations of stars based on their metallicity, naming the young, high velocity stars in the disk Type I and the older, red stars in the bulge Type II. This nomenclature was subsequently adopted for stars within the Milky Way, and elsewhere. [1]

Formation and history

According to a team of astronomers reporting in 2010, M31 was formed out of the collision of two smaller galaxies between 5 and 9 billion years ago. A paper published in 2012 has outlined M31's basic history since its birth. According to it, Andromeda was born roughly 10 billion years ago from the merger of many smaller protogalaxies, leading to a galaxy smaller than the one we see today.

The most important event in M31's past history was the merger mentioned above that took place 8 billion years ago. This violent collision formed most of its (metal-rich) galactic halo and extended disk and during that epoch Andromeda's star formation would have been very high, to the point of becoming a luminous infrared galaxy for roughly 100 million years. Messier 31 and the Triangulum Galaxy (Messier 33) had a very close passage 2–4 billion years ago. This event produced high levels of star formation across the Andromeda Galaxy's disk – even some globular clusters – and disturbed M33's outer disk.

While there has been activity during the last 2 billion years, this has been much lower than during the past. During this epoch, star formation throughout M31's disk decreased to the point of nearly shutting down, then increased again relatively recently. There have been interactions with satellite galaxies like Messier 32, Messier 110, or others that have already been absorbed by M31. These interactions have formed structures like Andromeda's Giant Stellar Stream. A merger roughly 100 million years ago is believed to be responsible for a counter-rotating disk of gas found in the center of M31 as well as the presence there of a relatively young (100 million years old) stellar population.

According to recent studies, like the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy lies in what in the galaxy color–magnitude diagram is known as the green valley, a region populated by galaxies in transition from the blue cloud (galaxies actively forming new stars) to the red sequence (galaxies that lack star formation). Star formation activity in green valley galaxies is slowing as they run out of star-forming gas in the interstellar medium. In simulated galaxies with similar properties, star formation will typically have been extinguished within about five billion years from now, even accounting for the expected, short-term increase in the rate of star formation due to the collision between Andromeda and the Milky Way.

Satellites

Like the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy has satellite galaxies, consisting of 14 known dwarf galaxies. The best known and most readily observed satellite galaxies are M32 and M110. Based on current evidence, it appears that M32 underwent a close encounter with M31 (Andromeda) in the past. M32 may once have been a larger galaxy that had its stellar disk removed by M31, and underwent a sharp increase of star formation in the core region, which lasted until the relatively recent past.M110 also appears to be interacting with M31, and astronomers have found in the halo of M31 a stream of metal-rich stars that appear to have been stripped from these satellite galaxies. M110 does contain a dusty lane, which may indicate recent or ongoing star formation. In 2006 it was discovered that nine of these galaxies lie along a plane that intersects the core of the Andromeda Galaxy, rather than being randomly arranged as would be expected from independent interactions. This may indicate a common tidal origin for the satellites.[2]

Future collision with the Milky Way

The Andromeda Galaxy is approaching the Milky Way at about 110 kilometres per second (68 mi/s). It has been measured approaching relative to our Sun at around 300 kilometres per second (190 mi/s) as the Sun orbits around the center of our galaxy at a speed of approximately 225 kilometres per second (140 mi/s). This makes Andromeda one of the few blueshifted galaxies that we observe. Andromeda's tangential or side-ways velocity with respect to the Milky Way is relatively much smaller than the approaching velocity and therefore it is expected to directly collide with the Milky Way in about 4 billion years. A likely outcome of the collision is that the galaxies will merge to form a giant elliptical galaxy or perhaps even a large disk galaxy. Such events are frequent among the galaxies in galaxy groups. The fate of the Earth and the Solar System in the event of a collision is currently unknown. Before the galaxies merge, there is a small chance that the Solar System could be ejected from the Milky Way or join M31.[3]

HGS Session References

HGS Sessions - Clearing Dorado, Leo Minor, Musca, Perseus constellations - 3/23/2015 [4]

References

- ↑ Andromeda Galaxy

- ↑ Andromeda Galaxy

- ↑ Andromeda Galaxy

- ↑ HGS Session

Found in HGS Manual on Page 108

Found in HGS Manual on Page 115