Book of Kells

The Book of Kells (Latin: Codex Cenannensis; Irish: Leabhar Cheanannais; Dublin, Trinity College Library, sometimes known as the Book of Columba) is an illuminated manuscript and Celtic Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables. It was created in a Columban monastery in either Ireland or Scotland, and may have had contributions from various Columban institutions from each of these areas. It is believed to have been created c. 800 AD. The text of the Gospels is largely drawn from the Vulgate, although it also includes several passages drawn from the earlier versions of the Bible known as the Vetus Latina. It is regarded as a masterwork of Western calligraphy and the pinnacle of Insular illumination. The manuscript takes its name from the Abbey of Kells, County Meath, which was its home for centuries.

The illustrations and ornamentation of the Book of Kells surpass those of other Insular Gospel books in extravagance and complexity. The decoration combines traditional Christian iconography with the ornate swirling motifs typical of Insular art. Figures of humans, animals and mythical beasts, together with Celtic knots and interlacing patterns in vibrant colours, enliven the manuscript's pages. Many of these minor decorative elements are imbued with Christian symbolism and so further emphasise the themes of the major illustrations.

Origin

The Book of Kells is one of the finest and most famous, and also one of the latest, of a group of manuscripts in what is known as the Insular style, produced from the late 6th through the early 9th centuries in monasteries in Ireland, Scotland and England and in continental monasteries with Hiberno-Scottish or Anglo-Saxon foundations. These manuscripts include the Cathach of St. Columba, the Ambrosiana Orosius, fragmentary Gospel in the Durham Dean and Chapter Library (all from the early 7th century), and the Book of Durrow (from the second half of the 7th century). From the early 8th century come the Durham Gospels, the Echternach Gospels, the Lindisfarne Gospels (see illustration at right), and the Lichfield Gospels. Among others, the St. Gall Gospel Book belongs to the late 8th century and the Book of Armagh (dated to 807–809) to the early 9th century.

The Abbey of Kells in Kells, County Meath had been founded, or refounded, from Iona Abbey, construction taking from 807 until the consecration of the church in 814. The manuscript's date and place of production have been subjects of considerable debate. Traditionally, the book was thought to have been created in the time of Columba, possibly even as the work of his own hands. This tradition has long been discredited on paleographic and stylistic grounds: most evidence points to a composition date c. 800, long after St. Columba's death in 597. The proposed dating in the 9th century coincides with Viking raids on Lindisfarne and Iona, which began c. 793-794 and eventually dispersed the monks and their holy relics into Ireland and Scotland.[2]

Chi Rho Monogram

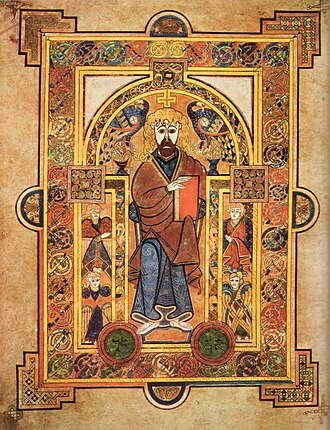

The Gospel of Matthew begins with a genealogy of Jesus, followed by his portrait. Folio 32v (top of article) has a miniature of Christ enthroned, flanked by peacocks. Peacocks function as symbols of Christ throughout the book. According to earlier accounts given by Isidore of Seville and Augustine in The City of God, the peacocks' flesh does not putrefy; the animals therefore became associated with Christ via the Resurrection. Facing the portrait of Christ on folio 33r is the only carpet page in the Book of Kells, which is rather anomalous; the Lindisfarne Gospels have five extant carpet pages and the Book of Durrow has six. The blank verso of folio 33 faces the single most lavish miniature of the early medieval period, the Book of Kells Chi-Rho monogram, which serves as incipit for the narrative of the life of Christ.

At Matthew 1:18 (folio 34r), the actual narrative of Christ's life starts. This "second beginning" to Matthew was given emphasis in many early Gospel Books, so much so that the two sections were often treated as separate works. The second beginning starts with the word Christ. The Greek letters chi and rho were normally used in medieval manuscripts to abbreviate the word Christ. In Insular Gospel books, the initial Chi-Rho monogram was enlarged and decorated. In the Book of Kells, this second beginning was given a decorative programme equal to those prefacing the Gospels, its Chi-Rho monogram having grown to consume the entire page. The letter chi dominates the page with one arm swooping across the majority of the page. The letter rho is snuggled underneath the arms of the chi. Both letters are divided into compartments which are lavishly decorated with knotwork and other patterns. The background is likewise awash in a mass of swirling and knotted decoration. Within this mass of decoration are hidden animals and insects. Three angels arise from one of the cross arms of the chi. This miniature is the largest and most lavish extant Chi-Rho monogram in any Insular Gospel book, the culmination of a tradition that started with the Book of Durrow.

Purpose

The book had a sacramental rather than educational purpose. Such a large, lavish Gospel would have been left on the high altar of the church and removed only for the reading of the Gospel during Mass, with the reader probably reciting from memory more than reading the text. It is significant that the Chronicles of Ulster state the book was stolen from the sacristy, where the vessels and other accoutrements of the Mass were stored, rather than from the monastic library. Its design seems to take this purpose in mind; that is, the book was produced with appearance taking precedence over practicality. There are numerous uncorrected mistakes in the text. Lines were often completed in a blank space in the line above. The chapter headings that were necessary to make the canon tables usable were not inserted into the margins of the page. In general, nothing was done to disrupt the look of the page: aesthetics were given priority over utility.